Blimey, talk about the emperor's wardrobe. Look around, and PR professionals will quickly come across a new-ish crop of pseudo-science which is supposed to guide them as to what their trade is and how to do it. They shouldn't need the warning. But some, such as participants in The Holmes Report's recent Global Public Relations Summit 2012 in Miami, who discussed 'Persuasion, Empathy, and Neural Coupling' and 'Unlocking the Brain’s Secrets About Creativity And Decision Making', seemingly need it stated plainly. This stuff is likely to be claptrap.

The social sciences often get in a muddle when they pretend to be scientific. Economics, sociology, history and pre-history, all blaze the trail here. Public relations, a trade steeped in conflicted logic and rhetoric and impressions if ever there was one, ought to be very nervous when its practitioners affect to have a scientific underpinning.

One of the arguments for PR to adopt neuro-scientific findings is precisely to spot the partially hard-wired human characteristics that define what Richard Dawkins calls our cultural memes, which explains all evolution (social and biological) by the differential survival of interacting self-replicating viral-like entities. This outlook is premised on a primitive materialist understanding of human nature, not to mention neo-eugenic theories. It is a viewpoint that maintains that human society is largely the product of pre-programmed (or re-programmable) mind- and fuzzy cultural-genes; in other words, evolutionary psychology. It leads many to believe that science can fathom our world so that PR pros can nudge the right triggers (neural, genetic, cultural) to get people to behave in a predictable, controllable and/or desired manner.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with the science of eugenics (nor with epigenetics) in principle: among other potential benefits, it allows us to eradicate some very awful inherited diseases such as Down’s syndrome. But we should worry when the research of neuroscientists or geneticists aims, or claims, to give scientific weight to ideas that are the social product of prejudice, politics and culture, or which are philosophical in content. In the 20th century, as we all know, some very backward - and nowadays totally discredited - beliefs and ideologies were once said to have had a scientific validity rooted in our supposed ingrained sociobiological make up.

The question is just how much can we rely on quantitative behavioural measures and neuro-scientific insights into our brain patterns to assess qualitative human variables such as our opinions and feelings.

There is a school of PR thought that promotes to clients the predictive power of algorithms and neuro-science to assist in identifying the 'relationship value' of networks amongst an institution's stakeholders. Professor Toni Muzi Falconi advanced such thinking on PR Conversations in his piece 'Improving stakeholder relationships through nets, neuros and algorithms', saying:

"Computer science allows the use of algorithms, which greatly reduce the need to research more than small samples of stakeholder groups. Likewise, neuroscience allows the integration of qualitative and quantitative indicators, which are closely connected to how relationships influence one another."

Describing what he is looking for, he adds:

"Interactions within stakeholder groups (or between the groups) can reveal – through graphics – the primary relationship nodes, as well as their interconnections. A mathematical analysis of these networks, supported by computer-led software, offers the essential numerical elements of specific indicators/variables."

I accept that in a digital world we can trawl for lots of interconnected data. Yet it would be a big mistake to read too much meaning into what's revealed. As Heather Yaxley commented on PR Conversations:

"Whether or not we have relationships with brands and whether or not they can, or should be trying to map our relationship is equally problematic. For example I am not a great fan of Carphone Warehouse generally, but it gave great service in replacing my Blackberry. So what does this mean? Nothing. I don’t care about the company, don’t want it to engage me, build a relationship, etc. It provided a service when I needed it – end of story."

She, not for the first time, is spot on. However my concerns, and I suspect hers, run much deeper. There is something potentially very dangerous and worrying about this trend that puts PR in the hands of the latest psychological and sociobiological psuedo-scientific theories. For anybody who thinks I exaggerate, here's the first paragraph from a press release promoting Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science:

"Too much choice can be a bad thing—not just for the individual, but for society. Thinking about choices makes people less sympathetic to others and less likely to support policies that help people, according to a study published..."

It goes on to describe research findings which showed:

"Simply thinking about ‘choice’ made people less likely to support policies promoting greater equality and benefits for society, such as affirmative action, a tax on fuel-inefficient cars, or banning violent video games."

Hence, to persuade us to think the right way, make the right choices and reduce our levels of stress, these scientists advocate that PR pros should become master-manipulators of neural pathways. Under the guise of evidence-based PR, this is an approach to public engagement that justifies the efficacy of its strategies by citing results based on biased research findings, as Toni Muzi Falconi puts it: "[of no] more than small samples of stakeholder groups." For example, the same Association for Psychological Science press release cites Krishna Savani of Columbia University opining:

“'In America, we make choices all the time—in the cafeteria, in the supermarket, in the shopping mall,' Savani says. He wonders if, in the long run, all those consumer choices might have a cumulative negative impact by making people less sympathetic towards others and less concerned about the collective good."

Such prejudicial reasoning reinforces that of other neuro scientists and psychologists such as Barry Schwartz, who also say we are oppressed and made unhappy by too much choice and freedom. The logic of Savani, Shwartz and Co's proposition is that, with some major help from PR pros, society should seek to constrain competition relating to things, options and ideas. They maintain that it is both possible and desirable to manipulate the public's neurons and subconscious genetic programming to ensure that it adopts the right (as in their preferred) behaviour and worldview. This small elite, of course, unlike us more irrational beings known as the mass public, know what is and is not in the public interest.

Their message and that of their PR backers seems to be that capitalism, freedom and democracy are overrated. Contrariwise: I maintain that ethical PR depends upon its practitioners respecting the moral autonomy of different players by helping people make informed decisions. Put another way, the psychobabble which underpins trendy nudge theory rests on ethically suspect and untrustworthy, not to mention unscientific, foundations.

That's a point made convincingly by the physician, gerontologist and clinical scientist Raymond Tallis in Aping Mankind: Neuromania, Darwinitis and the Misrepresentation of Mankind. Tallis pulls apart Richard Dawkin's neo-Darwinian explanations of human consciousness by exposing its degrading account of humanity's uniqueness. In summary, Tallis's book in defence of scientific integrity, which lauds and explains neuro-science's progress, at the same time exposes neo-neurobabble, as well as biological accounts of culture that maintain 'we are our brains' and which reduce self-consciousness to a mirror of biologism.

That's why I have to applaud Andrew Mayne's piece on Matt Ridley's The Rational Optimist where Mayne said that psychobabble spreads when the scientific community lets rip by assuming:

"... their expertise in their own field also gives them a proficiency in totally unrelated areas like economics and political science. Add in group reinforcement from their peers and you have a group of politically and religiously homogenized people who have very different ideas from you and I on what exactly 'the public good' means."

I have also to concur with Mayne's view that:

"Market theory, evolutionary psychology and neuroeconomics have reinforced what Adam Smith already told us, that the best measure of what brings about the public good isn't found in measuring just one choice, it's the cumulative effect of all the different choices that we make as a society. Choice causes anxiety, but it's an important part of being a human and not a member of an ant colony."

Having said that, up to a point I suppose that PRs and marketers do indeed, as professor Falconi says, rely on the usefulness of algorithms. For instance, our supermarket loyalty cards and our behaviour on Google allow for useful data-mining to predict what we might be interested in in future. The more supermarkets know about which types of consumers buy which types of products and when, the better they can serve their customers. Moreover, Google's entire business is rooted in the smart use of algorithms, which we all manipulate to influence search engine optimisation to get the messages of our clients at the top of the pile.

But we shouldn't get carried away the way that Google's Eric Schmidt does. He believes that his company's algorithms can really see inside our minds. He says Google can take serendipity out of the equation. Moving on from telling us how Google is run, he implies that its model could be used to organise the world economy. It could, he believes, enable society to predict electronically in advance what consumers will desire and want in the future. The logical implication being that capitalism can do what communism aims to do, which is to plan production in a conscious fashion; in Schmidt's world, by seeing into our "unconscious" minds to discover what will soon become a concrete demand.

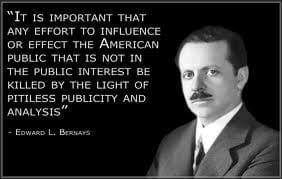

If I may wander for a moment, Schmidt's view is very Edward Bernays. Now I admire - and sometimes defend - Bernays. He was clever and insightful, but he was a propagandist: a manipulator. His ideas were in tune with - and perhaps inspired - propaganda techniques on both sides of WW2 and the Cold War. And he used it to flog stuff. It is true that he deliberately used ideas about the "unconscious" - ideas which he got from his uncle Sigmund Freud. I could argue (in line with keeping science out of PR) that the unconscious is a pre-scientific idea as old as the Greeks' Psyche, and their sophisticated understanding of art and illusion: so he wasn't all that scientific or original really. I'd rather argue that when propagandists hope to deploy scientific canniness in the media world to influence mass opinion, I hope and believe good old political prejudices (not 'scientific' ones), and insightful ideas and reasoned argument will, if they are allowed to, see through the guff. The success of the Bernays-Goebbels axis was not the success of science, not even in its Freudian form, but the failure of the German mass-mind to detect bollocks.

Ok, now that's off my chest, let's get back to Schmidt. He believes that most people don’t want Google to answer their questions, but to tell them what they should be doing next. But he sees this as involving more than providing choices. Schmidt views it instead as others deciding (taking the risk and guess work out of the marketplace) in advance which choices we will make:

“The power of individual targeting—the technology will be so good it will be very hard for people to watch or consume something that has not in some sense been tailored for them [in advance].

Though that only works - if for one moment we suspend disbelief and imagine it ever could - if Google plays the role of the communist centralised state by exploiting (and retaining) its de facto monopoly on internet search, aggregation and interaction. But I feel comfortable in saying that will never happen. It won't happen for the same reason that Schmidt's reasoning is flawed. Innovation, competition and new risk-taking continually redefine the human experience in new and unpredictable ways, the way Compaq, Microsoft, the internet and Google did recently.

Of course it is wonderful to see a modern capitalist like Schmidt saying that scientific and technological imperatives engineer choice out of consuming and uncertainty out of producing. But the hubris of the thing antagonises one. Doesn't he know life's more complicated than that? Doesn't he spot that if he was right, we might hate him and flock to a search engine that did stuff differently? It is at least intriguing to see a man predicting that what looks like the triumph of his business - information and individualism - is merely the triumph of manipulation. But hold on. This isn't really manipulation: it's anticipation as the word ought to be used. It's not all that creepy or conspiratorial so much as an expression of over-confidence.

Every business in the world takes a crack at getting ahead of the taste of its customers. For my money, the better they get at it, the better my life will be. And of course the genius of the modern world is that huge firms are getting better and better at working out the zillions of niches they have to cater to.

Anyway, you readily see, I think, that any claim that says human behaviour can be explained by, not to mention controlled by, the application of biological and neuro science is codswallop.

So in contrast to the PR utopians who promoted the benefits of neuro-scientific insights at The Holmes Report's Global PR Summit 2012, I maintain their claims are about as believable as the now discredited, but recently fashionable, idea, which suggested that computer-based equations devised by boffins could produce packages that strip the risk out of financial instruments and end the boom and bust cycle. So let people aim to map the human mass mind: I imagine they'll have all the luck which has attended those who try to map a single one.

For more on this from me see here.

Note: this is an updated essay which first appeared on this blog on April 1, 2011.

Become a subscriber receive the latest updates in your inbox.